Not All Humans?

The Hidden Power Dynamics Behind the Anthropocene Debate.

Dear friends and readers,

Welcome back to Our New Climate. Took some time off to focus on other things, including finding a new job and starting my coding journey. We are now back with renewed energy and a backlog of ideas… Here’s a quick preview of the themes for today:

When did we start expecting scientists to be prophets and problem-solvers, and what does this shift mean for the future of knowledge?

Why has the 'Anthropocene' become everyone's favourite buzzword, and what dangerous assumptions are we smuggling in when we use it?

With love,

Chloé

Dear Scientists: are we in need of a new social contract?

Never before have we asked so much of scientists.

At every crossroads, we look to science to help guide the choices we make, from climate change to public health.

The stakes couldn’t be higher: we’ve entered an era where scientific knowledge has become closely bound up with humanity’s survival in a climate-disrupted world (pretty stressful KPIs, honestly).

In response, voices are calling for a departure away from ‘normal science’ – that paradigm defined by Robert Merton’s classic norms of communalism, universalism, disinterestedness, and organised scepticism.

It’s increasingly obvious that in our critical present, science can no longer simply be about producing ‘objective knowledge’ in splendid isolation, divorced from real-world implications.

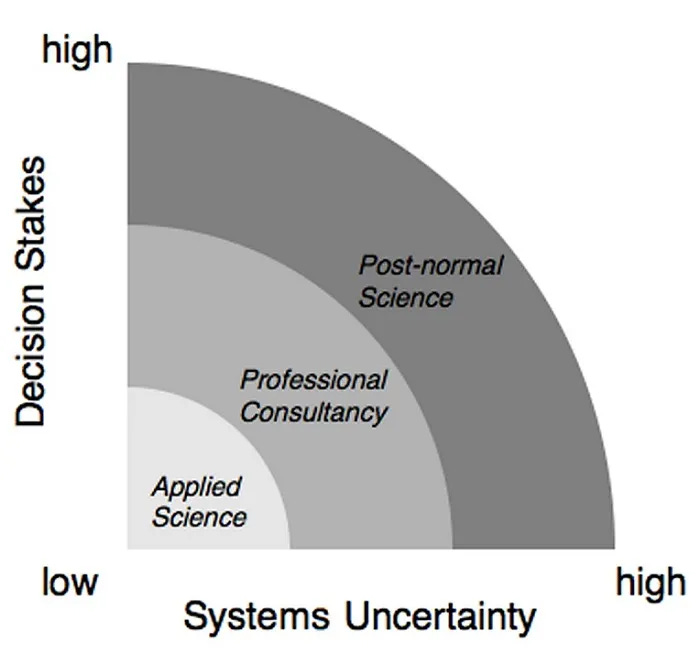

Silvio Funtowicz and Jerome R. Ravetz, architects of what they term ‘Post-Normal Science’, argue that traditional scientific processes are faltering in an age where "facts are uncertain, values in dispute, stakes high and decisions urgent".

I first encountered the concept of the ‘science-policy interface’ during my Masters, and it immediately transformed my perspective: policy, public opinion and knowledge production aren’t independent forces but rather deeply interwoven processes, embedded within specific power dynamics.

Climate change has made this complex relationship impossible to ignore, despite some communities’ stubborn efforts to maintain artificial boundaries.

And what better illustration than the ‘Anthropocene’ saga?

The Birth of an Epoch

February 2000, in sun-drenched Cuernavaca, south of Mexico City.

The Scientific Committee of the IGBP (International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme) — arguably one of the most influential scientific collectives you’ve never heard of — gathered for what would become a pivotal meeting.

For context: this group’s enduring legacy includes the revolutionary concept that Earth functions as a single self-regulating system, rather than a collection of independent processes.

As the story goes, Dutch Nobel Prize-winning atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen, exasperated by repeated mentions of the Holocene during this meeting, eventually burst into a fit of passion, begging his colleagues to see reality for what it is:

'Stop using the word Holocene. We're not in the Holocene any more. We're in the…the…the…[searching for the right word]…the Anthropocene!'

The Concept That Escaped the Lab

More than two decades later, the “Anthropocene” has taken on a life of its own, transcending its scientific origins.

It has cascaded from research papers to academic books, spilled into art galleries, saturated mainstream media, and even infiltrated the ‘About Us’ section of woke brands.

The term has become so ubiquitous that many missed the recent news: in March, a commission of experts officially rejected it.

Ever since Crutzen’s fateful outburst more than two decades ago, a working group has been quietly at work, assessing whether the Anthropocene deserved official recognition as the successor to our 11,700-year-old Holocene.

And if so, when did it start, and what stratigraphic markers might be used as evidence?

Decades of work culminated in the following precise proposal:

The Anthropocene began in 1952, marked by plutonium residues from nuclear bomb tests, preserved in the uniquely undisturbed sediments of Crawford Lake near Milton, Ontario.

The verdict? A decisive rejection: 12 votes against, 4 votes for.

Now, of course, in the grand scheme of things, none of this really matters. A group of geologists casting a vote (that some are questioning) is really a drop in the ocean considering how influential the concept has already become.

Yet this rejection might actually be a blessing in disguise. Freed from the constraints of formal geological classification, the Anthropocene is now back to us, to use and interpret in much deeper and broader ways that are infinitely more relevant societally.

The Hidden Dangers of Universal Terms

How can the Anthropocene become a useful framework for us?

Not using it at face-value is a good start.

My gripe with the Anthropocene is similar to that which I hold against any deceptively straight-forward notion: the importance always lies in the obfuscated details.

The surface-level notion that humans have triggered unprecedented and irreversible planetary changes seems straightforward enough.

But here lies the danger: concepts like these rely on an unexamined assumption of shared understanding, becoming chameleonic terms that adapt to any narrative.

This brings us to the elephant in the room: who exactly is the ‘anthropos’ in Anthropocene?

That’s something we almost never ask, yet the answer to this question reshapes the entire discourse.

By shrouding our ecological destruction under the blanket term ‘Anthropos’, we are universalising and diffusing responsibility to a state of near-meaninglessness.

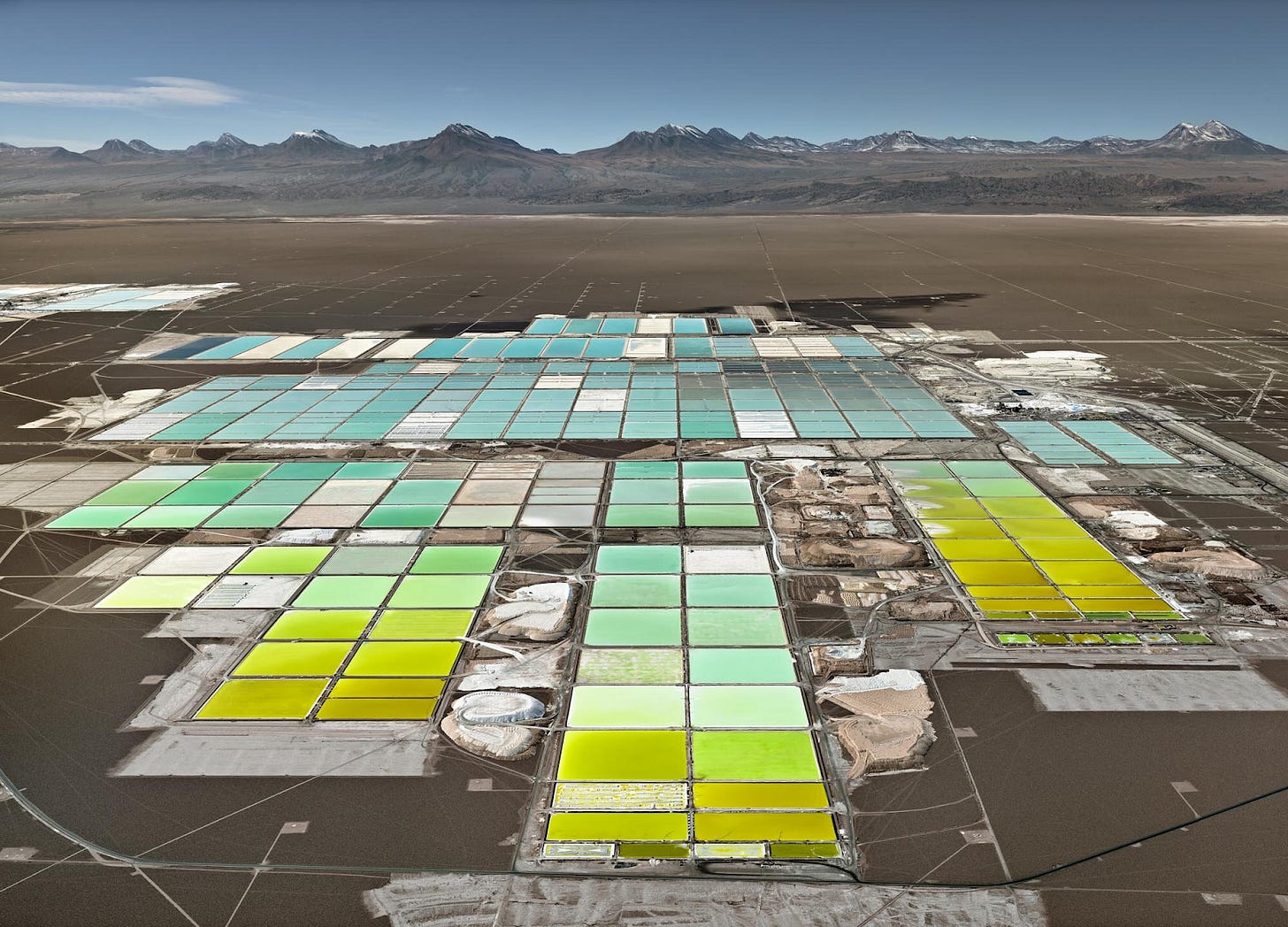

In practice, we are lumping together marginalised subsistence farmers with the men in suits who ordered the dropping of nuclear bombs. We are claiming that those sitting on the boards of extractive multinational companies are interchangeable with those living below the poverty line.

This seductive universalism — “we’re all in this together”, “humans did this” — conveniently deflects attention away from the particular power dynamics that have led us to this crisis.

Radical potential or Status Quo?

Is the ‘Anthropocene’ truly as radical as it seems?

As with other malleable terms, it can easily nest snuggly within harmful narratives, particularly those celebrating human exceptionalism.

It can be twisted into a story of civilisation reaching its zenith through technological prowess and intellectual advancement.

“We have become all-too-powerful, and the Anthropocene is the story of how we grapple with this power and the risks that come with it.”

There’s almost a whiff of twisted pride: we, almighty force of nature, have achieved the penultimate stage of evolution, bringing Nature to her knees.

Viewed this way, the Anthropocene merely reinforces Enlightenment-era narratives of control and subjugation — the very mindset that helped create our current predicament.

And it is precisely here that lies a massive, missed opportunity.

The Anthropocene could offer us a lens to finally recognise our fundamental interconnectedness with the living world. Instead of framing planetary collapse as either a testament to our unbridled power or our moral failings, we could see it as evidence of our undeniable interdependence with the living world.

That would be a truly radical break from business as usual – and perhaps the perspective shift we desperately need.

There's the capitalocene too. I haven't gone too far into that.

This is great and thoughtful! Have you checked out Paul Feyerabend's 'Against Method'? It seems quite relevant to your initial thoughts, in that he spoke often of a separation between science and the state (in the way many speak of church and state) due to precisely the interface you pointed out, particularly when it leads to empirically "self-evident" moral judgments in the policy realm.

As far as the geological disciplines from which the "Anthropocene" came to be, it may be worth mentioning the many other dendrochronological proxies that geologists have also used to argue in favor of indicating profound, measured, and cumulative effects attributed to the responsible subset(s) of humanity you described. At the time, I found the New York Times' reporting on the "rejection" of the term profoundly irresponsible in its emphasis and mischaracterization, but it is also clear that we are asking far too much of these terms, particularly in an era of context collapse and disingenuous interpretation. Thank you again!