Thawing permafrost and time flowing backwards.

You'll never look at your clock in the same way.

This is the tenth newsletter I’ve pushed out into the world since joining Substack. With each publication, deleted drafts, abandoned ideas — I’ve been able to see surprising truths emerge, about myself, my values and thought processes.

Writing changes you. It helps you slowly inch towards and grow into the most truthful version of yourself — or is it the other way around, peeling off the layers until you reach the core?

Regardless, it works.

A heartfelt thank you to the cosy two hundred (!!!) delightful human beings who have elected to read my work. I love writing for you.

Chloé.

I have somehow managed to go through 26 years of life on earth without a serious reflection about the notion of time, in and of itself.

I often think about time in relation to other things, like labor, capitalism, wealth, or mental health. But never have I paused to think about the watch on my wrist, the Japanese vintage Flip-clock that lives on top of my fridge.

Where do these artefacts come from? What they have done to my consciousness?

But a stray thought forced me to think more deeply about ‘Time’ as a concept: how we came to define time, the ways in which we chose to experience it, and what this choice says about us.

It turns out, there is a lot to think about.

Here’s a record of two weeks of feverish reflections (no metaphorical fever: I caught a cold) about how the climate crisis is turning our sense of time inside out, and why that might be a good thing.

Philosophising on feedback loops.

Climate feedback loops.

Definition: processes that either amplify or diminish the effects of climate forcings, starting a chain reaction that repeats endlessly.

Examples: forest dieback, ice-albedo feedback, permafrost thawing.

Feedback loops provide enough fodder to reflect on most philosophical questions that interest me: the limits of science, agency in nature, the self-destructive human urge to tame our environments, etc.

But what if feedback loops could also be a potent entry point to reflecting about time?

I’ve been obsessing about what’s happening to our permafrost: the up to 9 million square miles of permanently frozen ground spread mainly across Siberia, northern Canada, Alaska and Greenland.

While global attention focuses on the more visible signs of atmospheric warming — shrinking glaciers, thinning sea ice and stranded polar bears — we’re missing out on a whole other tragedy unfolding silently, right beneath our feet.

In direct response to our warming atmosphere — its effects being felt more intensely in the poles — the earth’s permafrost has been undergoing a slow yet inevitable process of thawing.

This process is one that scientists are watching very closely, because of the gravity of what’s stored within the permafrost: an estimated 1,400 gigatons of frozen organic carbon, or around four times the amount that we’ve emitted since the Industrial Revolution. Then there’s the indecent amounts of methane. Not to mention the ancient infectious diseases against which we are simply, not ready.

An endless cycle of more heating, more melting, more substances being released, more heating, more melting…

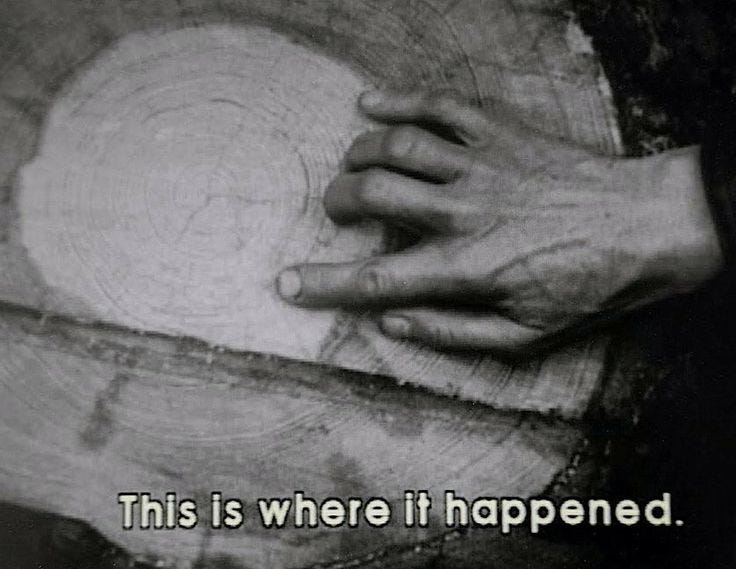

By disrupting our ecosystems at an unprecedented speed, climate change has opened various portals dispersed throughout the world, where the boundaries between past, present and future have become particularly… porous.

The past is re-entering the present, and screwing with our future.

The permafrost is a literal representation of this new normal.

What follows is not a comprehensive discussion of the history and politics of our conception of time (you might want to read this instead), but rather an attempt to scatter seeds of reflection.

Seeds that hopefully help me make the case that reflecting on this subject matter can actually strengthen our understanding of the climate crisis, and better equip us to respond.

You, dear reader, and the vast majority of our friends here probably subscribe to a linear conception of time, whether consciously or not.

‘Subscribe’ is probably not the best word, for it presupposes a choice, but you get my point.

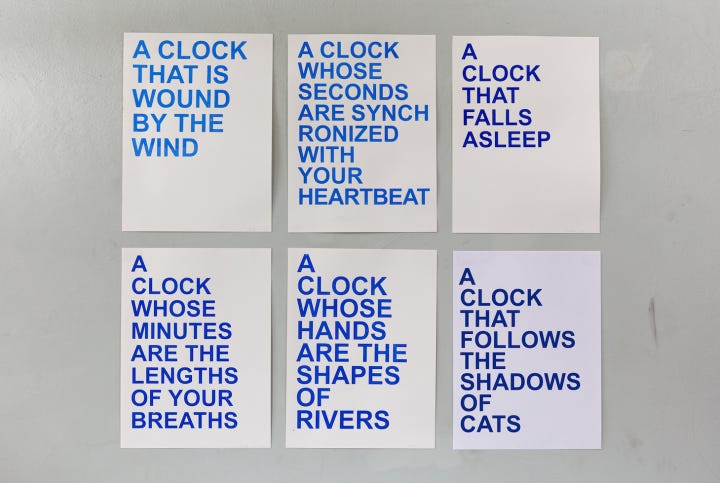

It is assumed that time moves forward, in a linear fashion, indefinitely and independently of our experience: a model we’ll refer to a ‘clock-time’.

It doesn’t take much research to find out that there are countless other ways of experiencing and understanding time across cultures:

It certainly helps to first destabilise the notion that clock-time is a universal, neutral and objective reality. It’s not. It’s a product of a specific culture, which has been enforced on a global-scale through a discrete yet violent history.

The single most successful machine in history?

Mechanical clocks are almost exclusively a European invention, rooted in the culture of the European Middle Age.

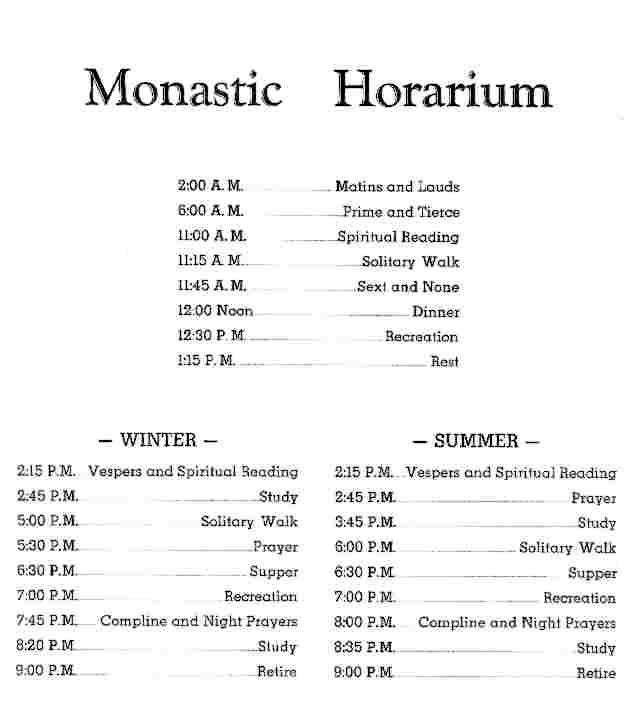

Timekeeping was of particularly high necessity in monasteries, where monks are required to worship and gather at regular intervals throughout the day.

Time here was communal, and could not be distinguished from its social context: 2:00am doesn’t mean anything outside of the fact that it signals the start of midnight prayer, also known as Matins.

In ‘Technics and Civilisation’, Lewis Mumford argued that judging by the depth and power of its transformational impact, the mechanical clock far out shadows the steam-engine as the symbol of industrial civilisation.

And what exactly did the mechanical clock achieves that’s so significant?

The technology is responsible for a fundamental change in our consciousness: the divorce of time from physical reality.

We no longer need to rely on the flimsy, unpredictable tools provided by nature: the sun and stars, cockerels crowing, birds singing, etc.

Think of 8 hour work shifts, two day weekends, lunch breaks at noon: countless individual and collective behaviours now follow a script that has no inherent meaning, no roots in physical reality.

A technology first developed to help monks keep time quickly transformed into a technology used to impose time.

The clock is a machine whose ‘product’ is seconds and minutes. As Mumford writes, ‘By its essential nature it dissociated time from human events and helped create the belief in an independent world of mathematically measurable sequences: the special world of science.’ (1934, 15).

In turn, the notion of time as abstract and linear has enabled specific cultural mindsets: infinite growth as an economic model would not exist in a society that subscribes to a cyclical model of time, for example.

Same goes for concepts we use everyday: investment, debt, along with binaries like developing vs. developed, primitive vs. civilised, etc.

What we lost in the process.

The grandest achievement of the mechanical clock has to do with the transforming of our perception of time, which we no longer view as a sequences of experiences, but as a collection of seconds, minutes, hours.

What are the implications of this shift, and how does it connect with the climate crisis?

During my research for this article, I came across and became fully enthralled by this wonderful record of how Australian Aboriginal communities have traditionally interpreted time.

Their temporal order is derived from their cosmology known as Dreamtime (or ‘the Dreaming’), which is shared by 16 major regional groups of Aboriginal societies.

One thing that stood out immediately, is the idea that time is something to be learned.

You would tell time not by glancing at your watch, but rather by observing the behaviour of species with whom you share your home: their seasonal feeding and breeding habits, patterns of migration, the arrival of certain blossoms, and so on.

One’s sense of time is derived from deep knowledge of the environment, achieved through minute observation and passed down generations.

Long before the division of the hour into discrete segments of 60 minutes and 60 seconds had taken over the European imaginary, Aboriginal people had developed a way of life based on based on a cyclical understanding of time. One marked by stages of birth, growth, death, replenishment.

‘When the time is right’

I learned that time is a crucial factor in defining the dynamic relationship between Aboriginal communities and the ecosystems they inhabit.

What time it is affects the movement of people across landscapes, the utilisation of resources, ritual gatherings, etc. There is a specific time for everything; a natural order that must be accomplished:

‘Being at the right time and in the right place was crucial, for if this did not happen, then they thoughts the earth would ‘harden’, and might not be a fruitful as it could be.’ (193)

Far from remaining passively symbiotic to their environments, Aboriginal communities had developed a strong sense of responsibility: that of ensuring that the cycles ‘continued to be circular’.

Perceptive readers will by now, i’m sure, exclaim: but we’ve broken our bond! the cycles have been disturbed, causing irreversible changes we’re struggling to comprehend!

My question is: could the steady retreat of cyclical time as a tool for organising society have something to do with the climate crisis? and on the flip-side, could rethinking our relationship with time consist of climate action?

Let’s connect the dots in part two. See you then!

It might also be possible that our view of time is a side effect of our mode of thought. That is to say, the same mode of thought caused an acceleration to climate change also happened to have a preference for a linear approach to time. There was a period where I lived without watches or clocks. Felt more natural. But it did not help if I needed to catch a train or coordinate with someone. I feel like the linear concept of time simply out competed our cyclical concept of time.

There’s another way of thinking about time that involves getting older. As you get older the period between seasons seems to go by faster. So at 26years you will see the years tick over at about half the speed as you do when you get to 52. In a similar vein, could it be that human written history only seems to be speeding up as the centuries tick over? Maybe that’s stretching it. But it could be said, as humans live to older ages, maybe our time concepts vary between individuals more and it becomes harder to get a consensus on things like climate change?

An interesting read. Thank you.

This is brilliant Chloe.. I study metaphysics and science and mythology and civilisations and natural order to things. I agree with you. The permafrost melting is a resetting of the nature clock. The earth has gone through 5major ice ages . The age of man followed the very last one 3 million years ago. We are a blimp in time. Our time may well be coming to a total end as the permafrost melts and sets off a cycle of rapid refreezing once the melting is complete. Do check my Substack out. You may read some synergies in our thinking . I wish you great success in your quest