Slow violence vs. the media

Paying attention to the unspectacular is hard, but it matters more than you think.

Sipping a decaf as I’m typing these words. Some days, you just want a steamy coffee, late in the day, without the insomnia.

Anyway, a warm welcome to part two of a short series on climate change and the question of time. For a deeper discussion of the relation between linear time and the anthropocene, please head over to part one.

Releasing in three, two, one…

— Chloé

What do all these have in common?

The steady reduction of wildlife abundance on Earth

The progressive thawing of permafrost in Siberia

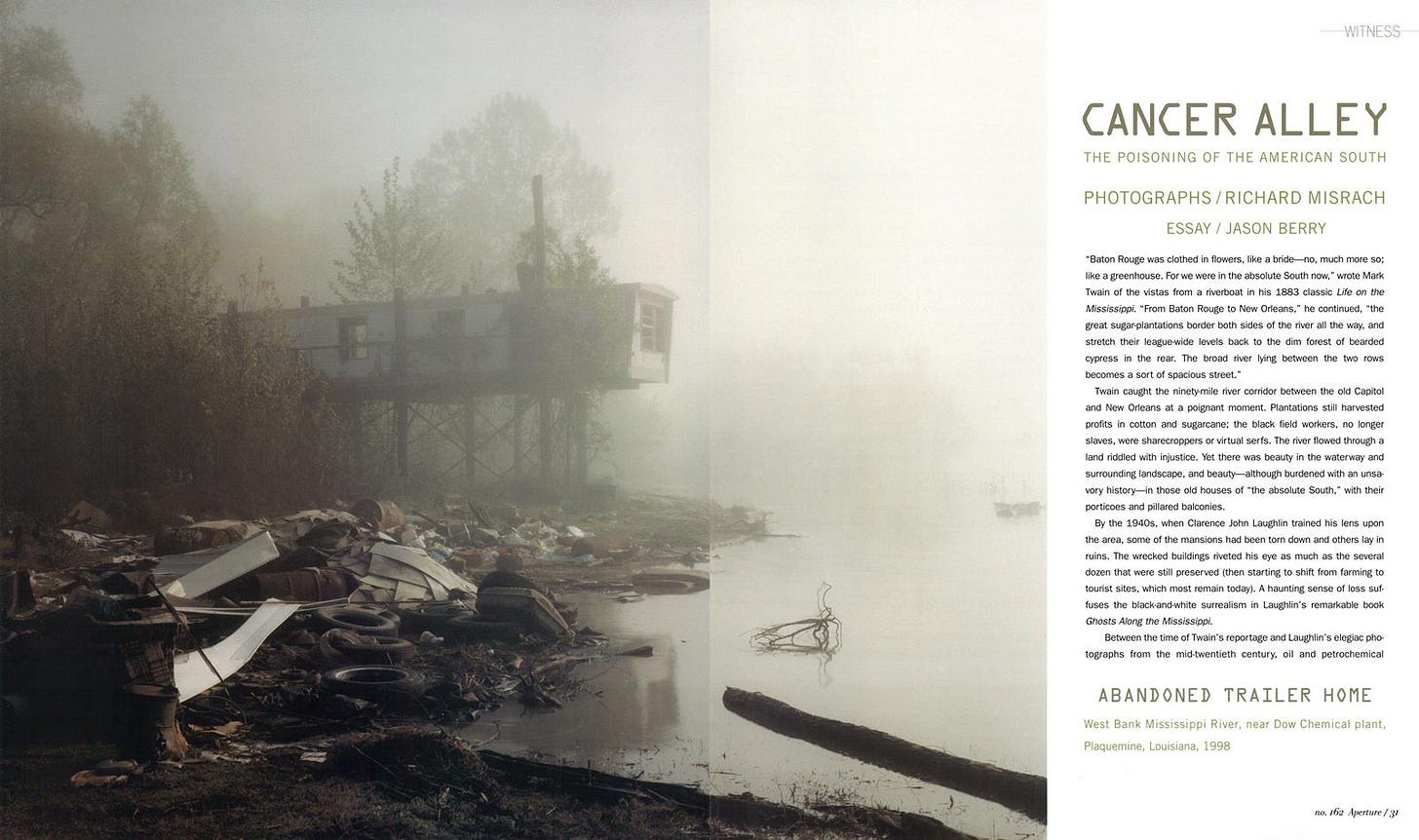

The somatic effects of chemical pollution in Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley’

All the above have contracted a severe case of spectacle-deficiency.

There is no event here.

At least not according to the standards of our entertainment-driven media. Just the quiet unraveling of environmental degradation, played out over months, years, sometimes decades. Hard to imagine, easily dismissed.

Getting to a point where we can talk about climate change in terms of crisis was a hard-fought battle, and an essential one.

But the question remains: what’s being obscured by the language of crisis?

The cult of the now.

Our linear conception of time, something we explored a little more deeply in part one, comes with a particular side-effect: the cult of the now.

The present has become the ‘only site of the real’ (Vázquez 2009).

We attend to fresh events more than those relegated to a distant past, under the assumption that the present holds more relevance to our lives and therefore, more importance.

By devaluing the past, we assume that time has a neutralising, softening effect.

But when it comes to environmental violence, time can have a rather sinister power: one defined by accumulation, intensification, and often, the blurring of causality.

The cult of the event.

We rely on events to ground our sense of time.

Dramatic events command our attention — we are particularly fond of those that gift us with a clear sense of before and after — explosions, declarations of war, pandemics, extreme weather events, etc.

Crises are so important to us that we’ve allowed them to shape our politics, as Naomi Klein has shown us time and time again with the twin concepts of ‘shock doctrine’ and ‘disaster capitalism’.

We use the power of crises to jolt us into action in our personal lives (how often have I waited for a serious health scare to really get my shit together…) — so how could it be any different in the public arena?

Slow violence: imagining the imaginable

What if a phenomenon gave us no spectacular event, but rather a slow and indefinite unraveling?

This is a question towards which Rob Nixon has dedicated decades of thought, crystallised in his ground-breaking work ‘Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor’ published in 2011.

Back in 2011, the year of Slow Violence’s publication, our eyes were riveted on the second worst nuclear disaster that took place in Fukushima, floods claiming hundreds of lives from Thailand to the Philippines, droughts that killed 100-500 million trees in Texas alone — all while the world population ticked over 7 billion.

Meanwhile, Nixon was researching something less tangible: the fallout of the 2003 Iraq war.

To be more precise: the environmental repercussions of depleted uranium, a radioactive metal deployed to increase the penetrating power of munitions.

‘Who is counting the staggered deaths that civilians and soldiers suffer from depleted uranium ingested or blown across the desert? […] Who is counting the victims of genetic deterioration — the stillborn, malformed infants conceived by parents whose DNA has been scrambled by war’s toxins?’ (Nixon, 2011)

He had planned to dedicate a short book on the matter, but was faced with obstacles: beyond the depressing nature of the subject matter, this was also one that proved complicated to pin down.

Instead, he lingered on what made this form of environmental injustice so challenging in the first place:

Slow violence is ‘a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all’ (Nixon, 2011)

Since then, a rich field of research has sprung around the notion of slow violence and its intersection with structural violence, significantly broadening the scope of environmentalism in the process.

Yet slow environmental violence still lives largely outside of the media spotlight.

Why?

I’ve just finished reading Neil Postman’s ‘Amusing Ourselves to Death’ — an unexpectedly delightful companion to this week’s topic.

So, in honour of Postman, I’ve decided to frame my discussion of slow violence through the prism of media’s influence on our ability to perceive, attend to, and therefore care about the unspectacularly insidious manifestations of climate change — and why that might matter.

Death of context.

Reading Postman’s ‘Amusing Ourselves to Death’ is a welcomed reminder of the scale and depth of television’s influence on public discourse.

But its effects would have been less pronounced if it weren’t for the foundation set by another technological innovation: the telegraph.

‘The telegraph made a three-pronged attack on typography’s definition of discourse, introducing a large scale irrelevance, impotence and incoherence.’

In Postman’s words, the technology legitimised ‘the idea of context-free information’, normalising the idea that ‘the value of information need not to be tied to any function it might serve in social and political decision-making and action, but may attach merely to its novelty, interest, and curiosity.’

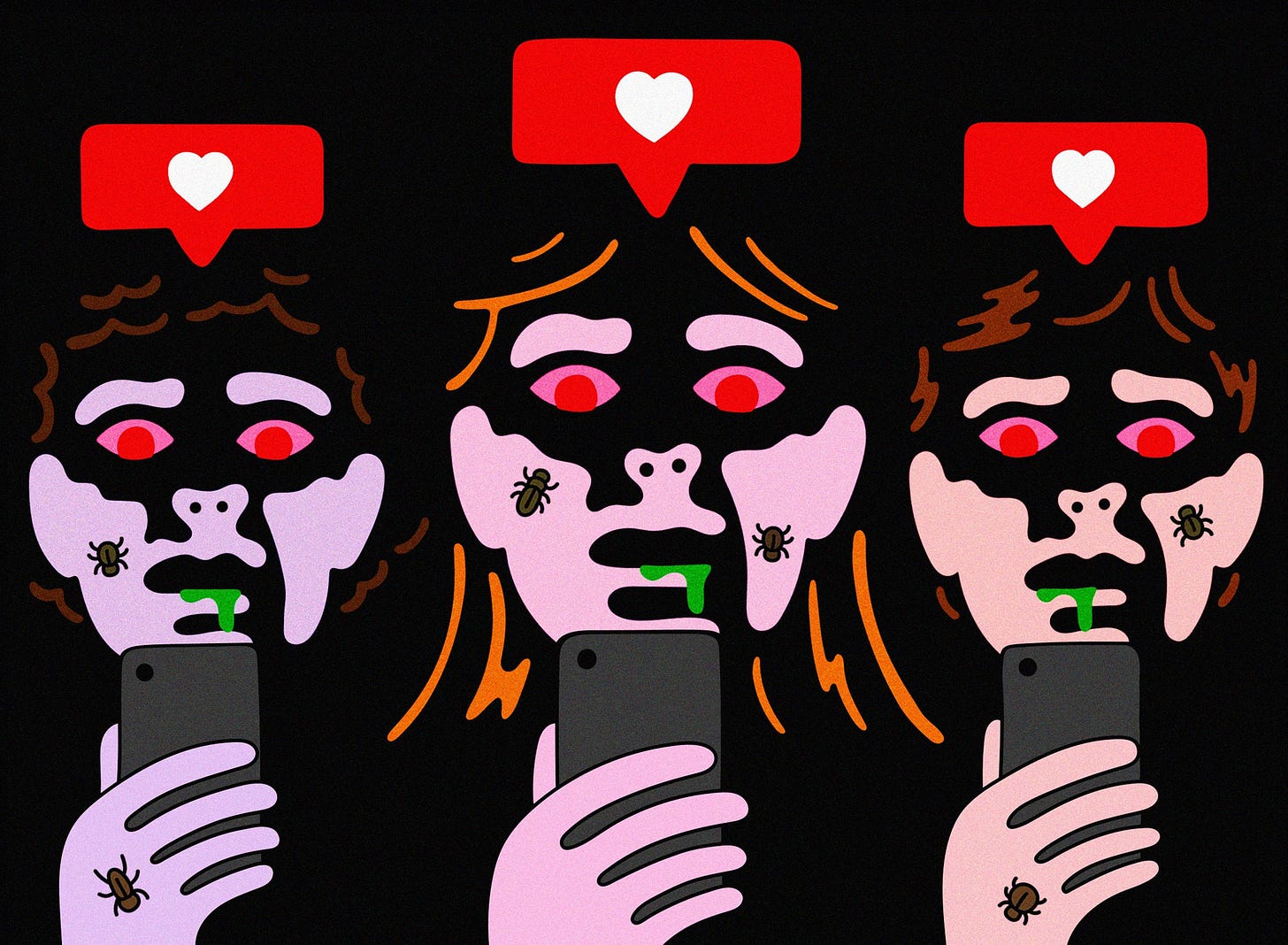

Long gone are the days of hyper-local news. We are now swimming in a cesspool of fragmented, incoherent info which we lack the time and resource to fully make sense of.

In a word: context is dead.

But what is context, if not the only way for us to process information, put things in perspective and extract meaning?

Passive consumers of information.

The media industry has turned us into passive consumers of information.

This was first achieved by filtering the type of information we have access to (context-free), and then the level of engagement required from us (shallow).

To think that Postman’s critique is limited to old fashioned television would be a mistake.

It’s plain to see that the requirements of televised media have seeped into all forms of mass communication (just think about how every platform under the sun has felt the pressure to roll out some kind of short-form video offer).

But even in mass media that still relies on the written word, we find the language of the spectacle all over: emphasis on memorability, shock-factor, emotionally-arousing and visually-arresting content, etc.

Stimulation, stimulation, stimulation!

Unsurprisingly, all of this makes it extremely hard to attend to the subtle and unglamorous manifestations of climate change.

We desperately wait for tipping points and disasters so we can point to them and say ‘Hey, I think it’s time we do something!’

Responding to climate change requires rethinking our current modes of public discourse, the structure of our media ecosystem, and addressing the biases that shape our perception.

This matters because of the close relationship between slow violence and environmental racism:

70% of African Americans live within two to four miles of a Toxic Release Industry as of 2011.

The first US lawsuit to challenge environmental racism from 1979 showed that five out of five of Houston’s landfills were in predominantly Black neighbourhoods, same for six out of eight of the city’s incinerators.

Nature disasters have been found to widen wealth gaps: with white families seeing an increase in wealth due to generous reinvestment initiatives, while minorities communities lack the resources to rebuild.

We cannot possibly address the complex environmental injustices stemming from climate change, imperialism, neoliberal marketisation — if we don’t even have the language for it.

Recognising, understanding, and addressing slow violence is a cornerstone of equitable climate action.

Missed part one? Don’t fret. Here you go:

Thawing permafrost and time flowing backwards.

This is the tenth newsletter I’ve pushed out into the world since joining Substack. With each publication, deleted drafts, abandoned ideas — I’ve been able to see surprising truths emerge, about myself, my values and thought processes.

Love the engagement with Postman. It's so weird to think that television spelled the death of context, when today's digital media represent an even more radical diffusion of context.

You’re incredible. Thank you, Chloé. I’m so glad you write and that you write, more specifically, exactly as you do.